Expert panel discuss water resources and bushfire responses

Securing water supplies for towns and cities in the face of major bushfires could rely on the increased use of technology to more quickly identify fire events and increase the speed of response.

That’s one suggestion to come from a panel discussion on water security and disaster resilience coordinated by the University of Melbourne in February.

The first discussion in the University’s Water Security Series for 2020 featured three forest and hydrology experts discussing the effects of bushfires on water resources, chaired by Associate Professor Meenakshi Arora.

Panellists were Professor Patrick Lane and Associate Professor Gary Sheridan, both from the University of Melbourne’s School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, and Geoff Steendam, manager of hydrological risk and planning at Victoria’s Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP).

Responding to questions about improving resilience, Professor Lane said there were economic arguments to invest in advanced fire surveillance technologies to supplement government investment in controlled burning. This kind of approach could be particularly effective in protecting infrastructure, such as water catchments and reservoirs as well as towns.

He said there was no definitive evidence that controlled burning could prevent wildfires such as those experienced throughout southeast Australian during the past summer. These severe fires resulted from environmental factors that included extended drought and high temperatures.

“But [controlled burning] can slow the rate of spread when a fire first starts, if the conditions are right, providing a chance to get on top of it before it’s too big,” he said.

Panel participants identified three leading water-related impacts from fire: contamination of water supplies; destructive ‘debris’ flows from exposed terrain; and the changing structure of forests.

Professor Lane said in the short term, water flows into catchments could increase, with little vegetation remaining to trap and use rainfall – at least until the process of forest regrowth begins. And it would not be clear until at least spring 2020 exactly how much forest had been killed, and how much remained alive and capable of regenerating, despite extensive charring.

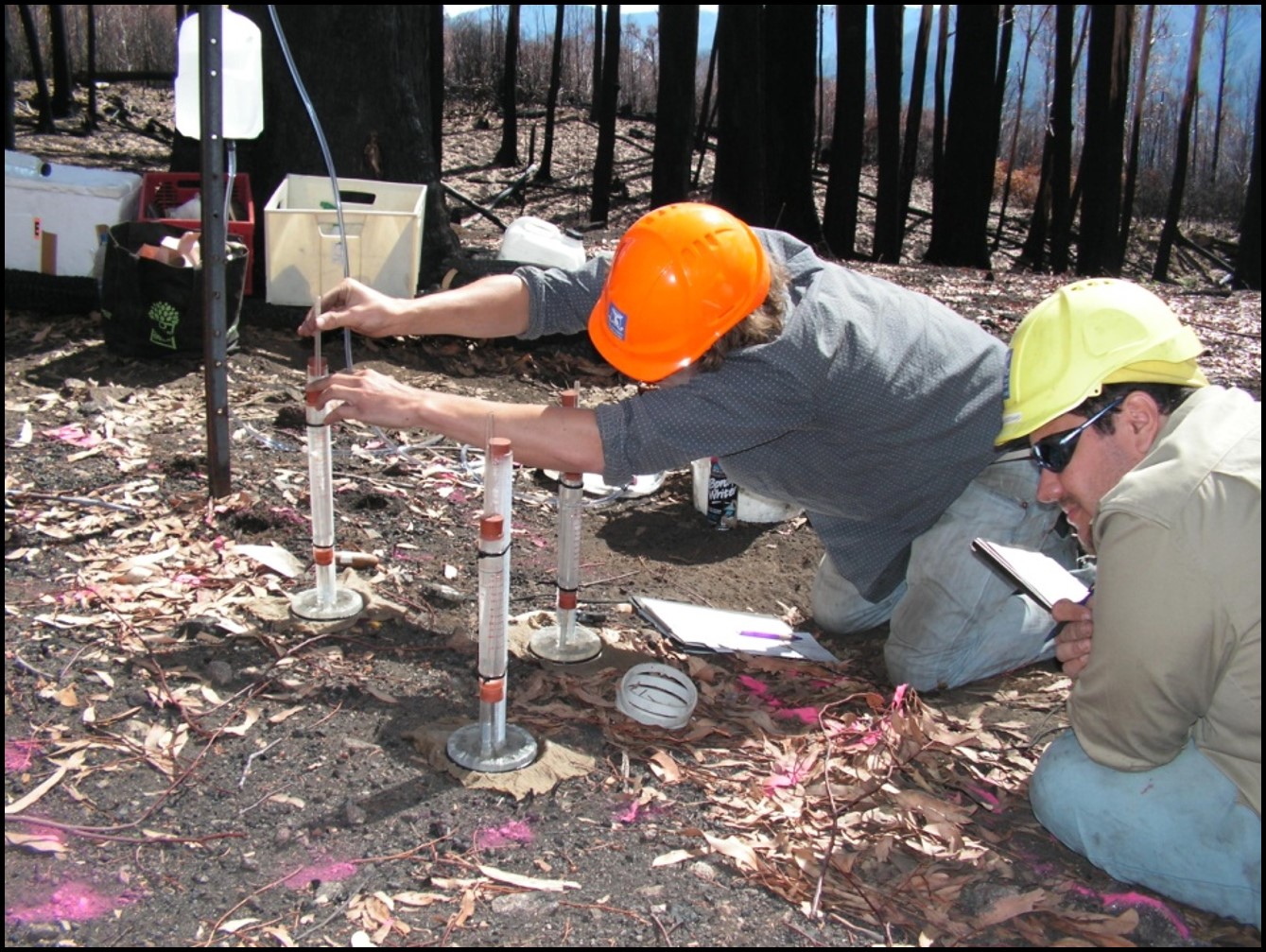

However, Associate Professor Sheridan said the exposed terrain, particularly in mountainous country, presented an increased risk of water supply contamination and dangerous debris flows, especially after heavy rain.

While contamination was a widely recognised issue, he saw debris flows as a potentially underestimated threat.

Burnt soils are highly hydrophobic, repelling up to 80 per cent of rainfall as runoff. And when intense storms occur, particularly on exposed, northern facing slopes, short-lived events can create torrential flows that are more akin to a fast-moving concrete slurry than muddy water.

Collecting sediment, soil, rocks and other debris, these flows can be deadly; one such event in California in 2018 killed 23 people. Similar, non-fatal events have also occurred in Victoria following fires, damaging roadways and isolating communities. Debris flows can be up to eight metres deep, and carry rocks of two tonnes or more.

Climate modelling also shows that the probability of triggering storm events is increasing.

Associate Professor Sheridan said stormwater flows of all kinds increased the potential contamination of water supplies, and Melbourne’s water supplies were at particular risk being located in heavily forested catchments.

Efforts to prevent fires in catchments were a critical first line of defence in protecting water supplies, which might involve upgrading the network of firebreaks and dedicated fire fighting forces, he said.

Hill slope and erosion treatments to prevent debris flows and building water filtration capacity at reservoirs could also help preserve water quality after an event. However, Associate Professor Sheridan recognised these works would cost billions of dollars.

Geoff Steendam from DELWP said modelling the long-term water availability for Victorian communities included the impacts of climate change and forest water use.

With four major fires in Victoria in the past 20 years, he said there was now a greater understanding of variations in water use by different types of forest as they recovered.

Geoff Steendam said DELWP was working with the Victorian Water and Climate Initiative to integrate climate and other influences on water availability, although bushfires were seen as having a minor impact.

All panel participants recognised the increasing frequency of fire was contributing to a change in the structure of the forests. Re-establishing after a fire, Mountain Ash requires at least 20 years to become sexually mature. If stands are burnt again within that timeframe, there will be no viable seeds to regenerate.

This could lead to more open, mixed eucalypt species establishing in former Ash terrain – creating more extensive areas of more highly flammable species, further exacerbating the fire risk, particularly combined with rising temperatures and reduced rainfall due to climate change.

And while current water availability modelling now better reflects climate change forecasts and forest water use during bushfire recovery, Professor Lane said changes in the structure of forests resulting from bushfires and related water use were yet to be factored in.