Engineering the future: people, place and partners

This is a transcript of the keynote address given by Melbourne School of Engineering Dean Professor Mark Cassidy at the World Engineers Convention 2019 held in Melbourne.

Professor Mark Cassidy speaks at WEC 2019

I would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation, who are the traditional custodians of this land. I also pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging and I extend that respect to other Indigenous people from around the world who are here today.

When I think about how universities can shape our future engineering and IT talent to create a better world, for me, it’s about people, places and partners.

These three Ps are the pillars supporting Melbourne School of Engineering.

We want to fill our University with bright, enthusiastic students from all over the world. And bright minds need dedicated educators and researchers to help inspire and challenge them.

Without clever and determined people like our students, academics, professional staff and colleagues we could not achieve what we do. Engineering and IT relies on collaboration and shared information.

Melbourne, one of the world's most liveable cities

We also need places – the research facilities, the teaching labs, the libraries, the cafes and the campus to run from one end to the other, trying to make it to a lecture on time. But a university is much more than just a campus.

We are all so lucky to work and live in Melbourne – one of the most liveable cities in the world. This sense of place is intrinsic to the University’s identity.

In addition to the fantastic food and coffee, we enjoy Melbourne’s arts and music scene, embrace multiculturalism, cheer on our favourite sports teams at the MCG and (I’m led to believe) spend far too much money choosing the best clothes to maintain our fashion reputations…

Melbourne’s identity influences the people who come to join us at the University - those inspired by culture and progression, those with a sustainable focus and those interested in change.

I’ve spent lots of time thinking about the role of our leaders – how as engineers our work is changing as the demand on our sector increases. And how we need strong partnerships with community, with our colleagues in industry, with our governments and with other research institutions.

So, sticking on theme, I’ll begin with people:

I would particularly like to acknowledge and celebrate Australia’s Indigenous engineers – connection to country and respect for the land and sea allowed Australia to thrive under Indigenous custodianship. We have a lot to learn from our First Nations people.

I am honoured to pay my respects to the Gunditjmara people from South Western Victoria – the home of the world’s first engineering project located at the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape.

Johnny Lovett chats to a drone operator at Budj Bim | Photo by Stu Heppell

The Budj Bim site is at least 6,600 years old – for context, that’s older than Stonehenge and older than the Pyramids of Egypt.

The site is made up of permanent stone houses, fish traps and infrastructure like channels and weirs used for breeding, growing and storing eels.

After 25 years of hard work by the Gunditjmara people, including intensive restoration of the site, we were delighted to see Budj Bim achieve World Heritage listing on 6 July this year.

It’s the first time an Indigenous led World Heritage application has been successful globally.

The Budj Bim site is at least 6,600 years old – for context, that’s older than Stonehenge and older than the Pyramids of Egypt.

The recognition was the result of a long campaign by the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and the Windamara Aboriginal Corporation, with support from Engineers Australia and the Victorian Government.

Budj Bim is the only Australian World Heritage property listed exclusively for its Aboriginal cultural value.

Melbourne School of Engineering has an enduring relationship with the Gunditjmara people. Our students are working with Gunditjmara Elders and rangers on community-led design projects.

Over several visits this year, our students and researchers, decked out in their wet weather gear, have headed down to South Western Victoria.

Students learn about Budj Bim on-site with ranger Tyson Lovett-Murray | Photo by Stu Heppell

They packed LiDAR scanners, robots, and aerial vehicles to map these ancient landscapes at Budj Bim.

So far, we have been able to digitally prove what the Gunditjmara have known for centuries – that their ancestors lived in a structured society with:

- permanent housing structures

- food smoking facilities

- water channels for trapping and storing food, and

- advanced river system management to ensure water was available throughout the year

We are using modern engineering methods to prove ancient knowledge about Budj Bim.

We appreciate being welcomed onto Gunditjmara country and we look forward to continuing our work together in the coming years.

It’s inspiring, isn’t it?

We are so proud to work with Indigenous communities to embed Indigenous perspectives into our teaching and learning, into the future of modern engineering.

We need our staff and students to better understand Australia’s history and gain knowledge from our oldest living civilisation.

At Garma Festival in August this year, our Vice Chancellor Professor Duncan Maskell announced the launch of the University’s Indigenous Knowledge Institute for world-leading research and education.

We’re committing $6m to this initiative.

The Institute will bring together leaders and innovators in Indigenous language, arts and music, life sciences, health, but also importantly engineering, IT and big data to showcase existing and emerging research. This is a new opportunity for knowledge exchange with Indigenous people globally.

We need our staff and students to better understand Australia’s history and gain knowledge from our oldest living civilisation.

It’s also a great opportunity to better know and include sustainable indigenous engineering practices into curriculum for our students.

Finding pathways for Indigenous students to study engineering at university is a big priority for us – and is one we share with our colleagues in other universities across this land.

This is why in Melbourne, each year, we join with Monash, RMIT and Swinburne Universities to co-host the Victorian Indigenous Engineering Winter School – or VIEWS as we affectionately call it.

The program is open to Indigenous Australian students enrolled in maths or science in Years 10, 11 and 12. We provide VIEWS students with a team of mentors, many of whom are alumni from the program itself.

Over the course of a week, students live on-campus with us, participate in hands on workshops, take site visits to our industry partnersand gain an understanding of the pathways available to study science and engineering at university.

We must continue to seek, inspire and support young Indigenous Australians who enjoy problem solving. Those who are interested in the latest tech and who want to use their skills to help shape the future.

2019's VIEWS students

We must also encourage Indigenous students to consider academic pathways – from Masters through to PhD candidature through to post-doctoral positions.

As engineers, we create our society through the application of science. And if the design of society reflects those who create it, then we must support diversity.

Our future engineering and IT professionals must represent a spectrum of socio-economic and cultural backgrounds.

But diversity is nothing without inclusion.

We welcome and value people from any religion, of any age, with any level of physical ability and of any gender identity at the University of Melbourne.

Boosting the number of women in engineering and IT is imperative.

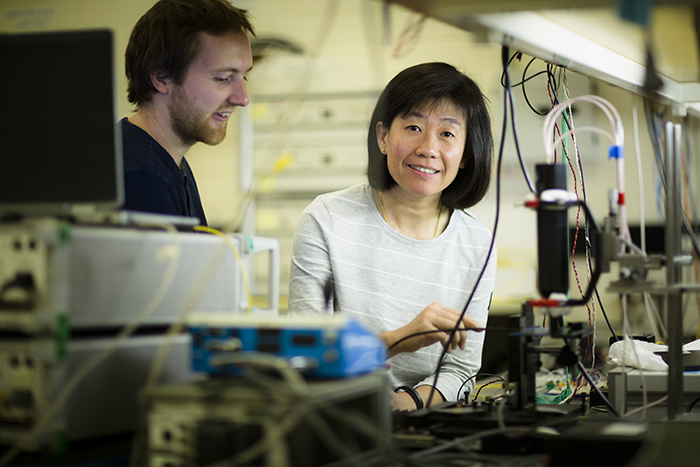

Professor Christina Lim

Australia’s engineering workforce is only 12 per cent female; a national disgrace.

While workplace retention and recruitment are issues the whole engineering profession must address, at the University level we’re also taking action to ensure our number of female students remains high.

We’re proud that more than 37 per cent of the 2019 intake are female; the highest figure of engineering schools in the country. though I know none of my Dean colleagues will rest until we have parity.

We need to create better and more flexible career paths for women. This year we launched the inaugural Doreen Thomas Post-Doctoral Fellowships, offering seven roles for early career researchers.

These fellowships, named after Emeritus Professor Thomas, former Head of Electrical, Mechanical and Infrastructure Engineering, will enable the seven talented recipients to undertake high quality, independent, multi-disciplinary research with access to ongoing financial support and mentoring.

We are very lucky to have Professor Thomas inspiring our next generation of engineers.

But creating a University full of vibrant, brilliant, diverse and interesting people is only part of our job. We also need to create the places for our people to thrive.

Melbourne is undergoing a period of immense change. And as the city grows, so too must we. Modern universities need to be part of the community.

Historically we were surrounded by walls to keep knowledge safe - but now the walls are coming down.

We’re broadening our reach outside our Parkville campus, joining industry colleagues in new technology and innovation precincts.

Historically we were surrounded by walls to keep knowledge safe - but now the walls are coming down.

By 2025, we will have invested a billion dollars to deliver Melbourne Connect Innovation Precinct and a new engineering and design campus at Fishermans Bend.

At Melbourne Connect we’ll have research, industry, government, students and entrepreneurs all under the same roof.

It’s a model of a future economy in a digital landscape.

Melbourne Connect will provide new opportunities across research disciplines to address some of society’s greatest problems.

The University’s Centre for AI and Digital Ethics is just one example. It brings together computer science, law and the arts. The Centre will support the fields of automation and AI systems to become fairer and more transparent.

As you’ve seen, we’re building Science Gallery at the base of Melbourne Connect, a place to explore and push the boundaries of arts and science. We will host events featuring global thought leaders and curate exhibitions on controversial themes.

Science Gallery has already tackled exhibitions about blood, perfection and waste - we can’t imagine what they’ll think of next!

Places like Melbourne Connect are edging us closer towards a future saturated with data. But are we prepared?

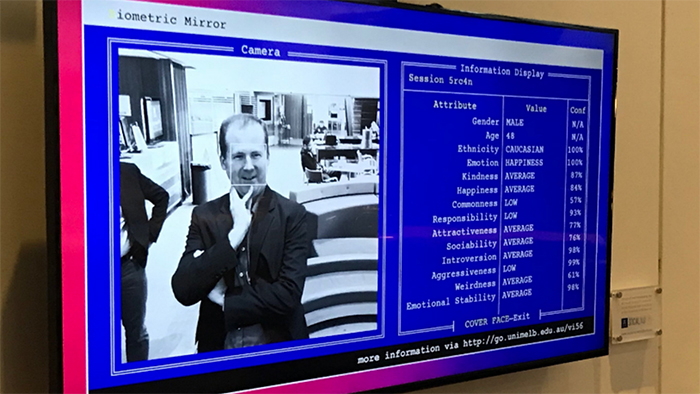

As part of Science Gallery’s Perfection exhibition last year, the University unveiled one of its most thought-provoking research examples – Biometric Mirror. And we’re happy to have it to show you here at WEC.

The interactive digital screen takes a real-time photo to detect your facial characteristics. Your photo is then compared to thousands of crowd-sourced head shots and reviewed for their perceived traits.

Professor Mark Cassidy receives his Biometric Mirror results

And as you can see, I’m a pretty average guy!

Biometric Mirror’s results range from gender, age to attractiveness, weirdness and even emotional stability.

The longer you stand in front of Biometric Mirror, the more personal the traits become. The thing about these results - they’re wrong. And they’re wrong to prove a point.

At this moment in history, technology has exceeded our ethical ability to keep up. Humans don’t have a great track record in saying ‘no’ to technology.

Biometric Mirror is just one example.

Law enforcement agencies in the US use driver’s license photos to identify criminal suspects and back home, Australian shopping centres are tracking our movements to better market their products.

At this moment in history, technology has exceeded our ethical ability to keep up.

We must remember that if we rely on the results generated by AI, we’re only as informed and diverse as the data sets used to train these systems.

Biometric Mirror suggests I have “low responsibility” and only “average kindness” - imagine if that had influenced the HR team assessing my application for the Dean role at the University!

Worse still, would you want your health insurer to see you had low emotional stability or your car insurer to see you were highly aggressive?

While these are all exaggerated examples, we saw some students react surprised when using Biometric Mirror – believing that when a computer told them these things, they must be true. Rest assured, we provided context for the reasoning behind the research.

I encourage you to visit the University of Melbourne exhibition stand here at WEC – it’s recommended you bring your own psych support!

Continuing our theme of place – we’re excited to be a partner in the Melbourne Biomedical Precinct, one of the world’s leading hubs for outstanding patient care, cutting edge research and innovation to train the next generation of medical professionals.

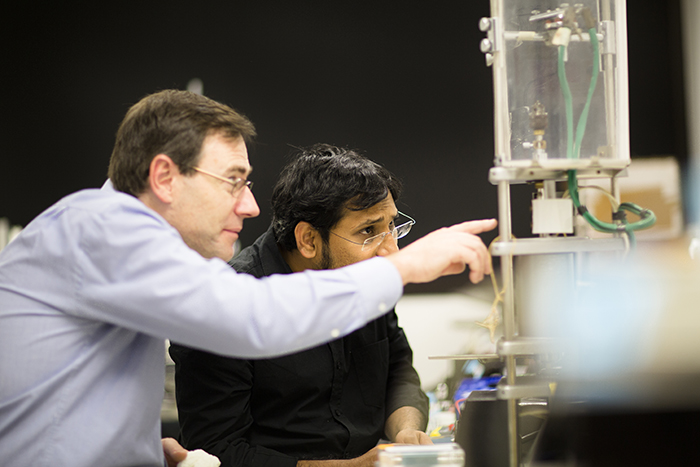

At the precinct, our electrical and biomedical engineers are working with colleagues in medicine to trial the use of brain stimulation devices to treat epilepsy, chronic depression, Parkinson’s Disease and paralysis.

These devices record and read our bodies’ electrical signals to predict when something is about to go wrong, triggering the device to respond appropriately. This could help get a patient to a safe place ahead of a looming epileptic seizure.

Cutting-edge innovation happens in a lab, but often, we need a lot of space. Space to design, build, test, break, rebuild, retest and eventually perfect.

Professor David Grayden and Dr Sam John working on Stentrode

So we’re out in the real world working on the ice shelves of Antarctica investigating the interaction with waves.

We’re in the Murray Darling basin helping to solve the ever-growing problem of water security.

At the Great Barrier Reef, we’re designing a chemical sunscreen to shield coral from further bleaching.

Even in Canberra, at Parliament House, we’re calling on the Australian Government to do better when it comes to cybersecurity. And we’re helping shape policy to legislate the digital world.

The University of Melbourne is building a completely new campus at Fishermans Bend to give us more of this space.

We’re part of Australia’s largest urban renewal project to accommodate 80,000 people and create 80,000 new jobs by 2050.

Fishermans Bend will bring to life our vision for energy that is affordable, reliable and sustainable.

The University of Melbourne’s new campus at Fishermans Bend is bringing research and industry together to tackle urgent global challenges in real-time and at scale.

We’ll have one of the world’s largest wave tanks, giant outdoor aerial drone nets, a virtual power plant for sustainable energy trials and space to stress-test futuristic civil engineering infrastructure.

For the first time we’re bringing the University to industry – locating alongside our key partners including Boeing and Defence Science Technology Group.

Fishermans Bend will bring to life our vision for energy that is affordable, reliable and sustainable. We’re going to build a large-scale virtual power plant to run the campus and potentially power the entire precinct incorporating renewable energy, battery storage, building services, zero emission fuels, hydrogen engines and sensor communications.

We’ll be testing these technologies in a real-world working environment.

Another example of large-scale testing at Fishermans Bend is AIMES, short for the Australian Integrated Multimodal EcoSystem – now you know why we call it AIMES!

With more than 50 global partners from government and industry we test smart IoT technologies to improve city mobility, enhance sustainability and most importantly keep us safe.

AIMES has set up a 6km2 test bed in Carlton; the most highly connected grid of roads, intersections, footpaths and traffic lights in the world mapped with sensor technologies.

We capture the movements of all road users in real-time. We’re looking forward to trialling autonomous vehicle technologies down at Fishermans Bend.

Like any global city, Melbourne’s traffic is getting worse and we need more innovative, big picture design for public transport and traffic. But it is really the use of data from AIMES that will make a big difference to how we move around.

Those blue brains are quite memorable!

The third pillar, and one I haven’t spoken about yet, is partners.

As engineers and IT professionals we design the infrastructure for roads, buildings and public transport, we create the networks which send millions of data points around the world every second. We are tackling climate change and providing sustainable energy solutions. We’re solving health problems with personalised medicine and we’re designing the emerging technologies which will help address our global demand for food and water as the population booms.

These challenges are increasingly complex and require a multi-disciplinary approach. We need large teams to come together in partnerships made up of innovative thinking, research expertise and industry knowledge.

As the world of work changes, our approach to teaching and learning must change too.

We need to work with government and policy experts to find and fund projects to drive benefit for society. And we need to work with communities to better understand how people live and what their needs are right now, and into the future.

As the world of work changes, our approach to teaching and learning must change too – our students are directly impacted by their learning environments.

Industry and academia already have a symbiotic relationship - our engineering and IT students expect industry experience as part of their tertiary degree. And industry looks to employ graduates who are ready to apply what they’ve learned in real-world scenarios.

Our talented graduates are our future leaders. Generation Z are expecting and demanding more from their education. Modes of teaching and learning, such as project-based curricula and blended online environments, are now just the basics.

The role of a university is to equip engineering and IT students with broad skills in problem-solving and communication and to nurture their entrepreneurial vision. There is growing emphasis on the ability to question and interrogate knowledge.

Students now gather their knowledge from anywhere – even from Donald Trump’s tweets if they like! Universities like ours have an important role to play in helping students decipher facts from fake news and to interrogate and apply data to their work.

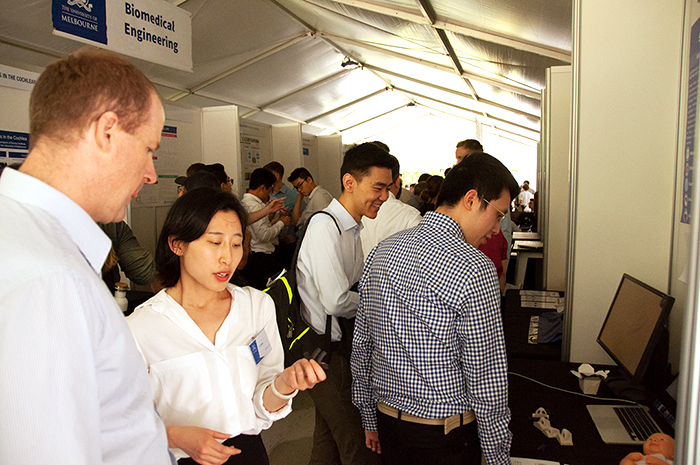

A student explains her Endeavour project to Professor Mark Cassidy

Initiatives like the University’s Endeavour Exhibition help bring our final year Masters students together in small cross-disciplinary groups designing products, services and ways of working, directly linked to industry needs.

One recent example involved a team of mechatronic and electrical engineering students who created smart technology to allow small and large agile drones to travel long distances together. This technology could aid search and rescue operations during bushfires or land and sea searches.

We had another Endeavour team produce a device to monitor cannulas during surgery. A cannula is the tube that delivers medication during a surgery.

This device gives anaesthetists a degree of confidence about the positioning to ensure patients remain asleep throughout surgery.

Increasingly, University of Melbourne students will experience research at its most practical level and actively contribute to the design of large-impact projects.

Another team developed a smart cane for the visually impaired. The smart cane uses sensors to map where someone is walking, provides vibrational guidance and will eventually reduce the reliance on guide dogs and distracting audio.

At the request of our students, we’re further embedding research into our curriculum. This provides dual value giving students access to real-time technical problems and smoother pathways into graduate research if they choose.

Increasingly, University of Melbourne students will experience research at its most practical level and actively contribute to the design of large-impact projects.

We’re excited to see this new wave of teaching and learning evolve at Melbourne Connect and Fishermans Bend.

An artist's rendition of Fishermans Bend campus from above

Our students and partners will benefit from each other - we know that industry wants to meet our talented students, and that our students want to get to know industry before dedicating themselves to a future career. It’s a win-win.

So, what’s next for engineering and IT? What does the future hold? We are facing unprecedented rates of climate change, population growth,water scarcity and rapid urbanisation - just to name a few.

As engineers and IT professionals, as educators and researchers, we have a responsibility to bring together people and partners in the right places to help solve the world’s problems through technical solutions.

It’s up to us to ensure future generations have the skills to adapt as new challenges emerge.

It’s up to us to work with government and industry to guide policy decisions which will position Australia as a global leader.

It’s up to us to work with our industry partners to push the technological boundaries for the benefit of all.

And it’s up to us as engineers and IT professionals to leave the world in a better place than we found it.

It’s a pleasure to be here today. Thank you.